If you’ve read my other Watership Down content, you’ll already know how I feel about the film. It’s a classic — but it hits hard. Both in book and film format. But are they sad in the same way? And what exactly makes Watership Down sad?

Contents

- Introduction

- The Sadness of the Book

- The Sadness of the Film

- Why the Film Feels Sadder (But Shallower)

- Shared Sadness Across Both

- Why Do We Still Search “Watership Down Sad”?

- Book vs. Film — Which Sadness Endures?

- Conclusion

Why is Watership Down So Sad?

If you ask almost anyone why Watership Down has stayed with them, the answer is simple: it’s sad. Traumatising, even. Even now, one of the most searched phrases in connection with the film is “Watership Down sad”. An attempt to try and process why a film about rabbits became one of the darkest childhood experiences of the 70s, 80s, and 90s.

And then there’s “Bright Eyes.” Art Garfunkel’s haunting ballad became synonymous with the 1978 film — a lullaby that felt far too beautiful and far too mournful for children’s television. For many, that song alone was their first taste of grief, loss, and the strange quiet beauty that comes with it.

But here’s the thing: the sadness of Watership Down isn’t the same across mediums. Richard Adams’ 1972 novel carries a slow, layered sorrow — an allegory of exile, leadership, and mortality. The film, on the other hand, condenses that into ninety minutes of blood and shock, forever branding it “the traumatising rabbit movie.”

So, which sadness cuts deeper — the novel’s quiet despair or the film’s violent trauma? Let’s explore how Watership Down’s sadness differs in book and film, and why both still haunt us today.

The Sadness of the Book

When Richard Adams began telling stories about rabbits to his young daughters on a long car ride, he probably didn’t imagine he was creating one of the most enduring works of modern literature. Watership Down (1972) has since been called everything from an animal adventure to a political allegory, but one thing is constant: its sadness.

In the novel, sadness creeps in slowly. We feel it in Fiver’s visions, in Hazel’s quiet wounds, in the rabbits’ exile after the destruction of their warren. The violence is there, but it unfolds in the mind’s eye rather than in splashy frames. Adams’ prose lingers on myth and metaphor — the Black Rabbit of Inlé, the chilling reminder of death’s inevitability.

“All the world will be your enemy, Prince with a Thousand Enemies, and whenever they catch you, they will kill you. But first they must catch you.”

This quote, from the rabbits’ creation myth, sets the tone: their lives are fragile, their world always threatened.

Yet Adams balances this sadness with resilience. Hazel’s leadership, Bigwig’s bravery, Fiver’s intuition — together they prove that even in the face of inevitable loss, there is hope, courage, and survival.

In the book, sadness feels philosophical. It’s not just about death, but about the cost of freedom, the fragility of safety, and the weight of leadership. That’s why adults who revisit the novel often find its sadness richer and more poignant than they remembered as children.

The Sadness of the Film

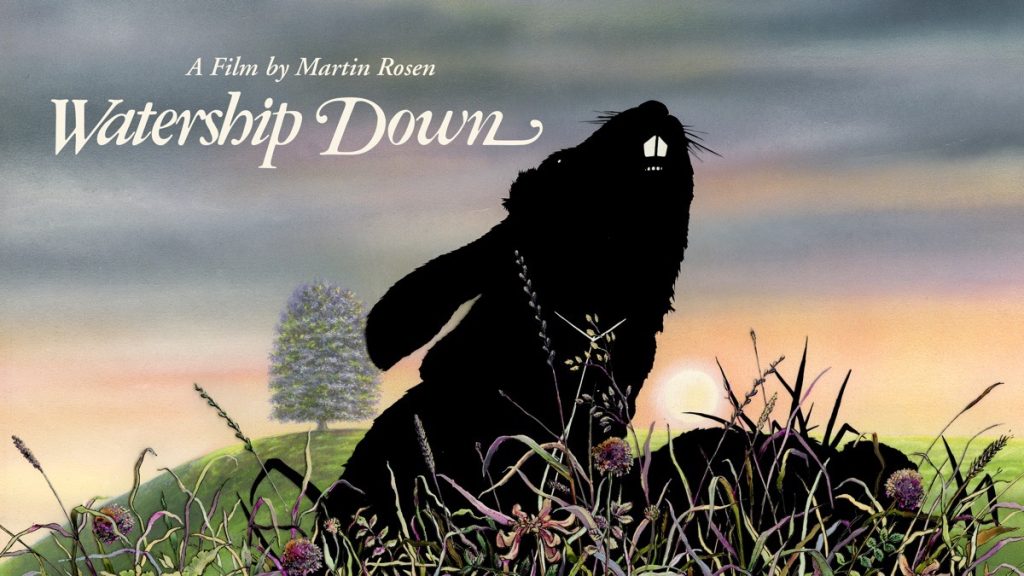

The 1978 animated film, directed by Martin Rosen, took Adams’ 400-page epic and compressed it into just over 90 minutes. What was gradual and layered in the novel became immediate and brutal on screen.

The sadness of the film is almost entirely visual. Dogs tear through rabbits. Blood smears across the grass. General Woundwort’s savagery becomes visceral. The images burn themselves into the memory of children who expected a harmless cartoon about bunnies.

That disconnect between expectation and delivery is why the film feels especially cruel. Its marketing leaned into colourful animation, the kind of thing parents assumed was safe. Instead, they sat through a barrage of shocking violence.

As Roger Ebert noted in his 1978 review: “The animation is beautiful, but the violence is unusual in animation, and one wonders at the wisdom of showing it to children.”

And then, layered over the imagery, came “Bright Eyes.” The film pauses to show Hazel drifting near death, Art Garfunkel’s voice soaring with:

“Bright eyes, burning like fire,

Bright eyes, how can you close and fail?

How can the light the burned so brightly

Suddenly burn so pale.”

It’s a haunting image that tugs in at the heartstrings in way that nobody could forget.

Why the Film Feels Sadder (But Shallower)

So why does the film leave such a heavier emotional scar than the book, when both tell the same story?

Part of the answer lies in the compression of time. Richard Adams’ novel has room to breathe. The rabbits endure hardship, but between each danger there are long passages of storytelling, camaraderie, and even humour. Readers are given time to process, to recover, to see hope blossom before the next challenge.

The film, by contrast, compresses hundreds of pages into an hour and a half. There is little room for levity or pause. Scenes of violence — rabbits strangled in snares, choked by smoke, or mauled by dogs — come hard and fast. For children watching, it felt relentless.

Another reason is the medium itself. Reading about Hazel being wounded allows the imagination to shape the scene. Seeing Hazel limp, bloodied and close to death on screen, while Bright Eyes plays in the background, is seared into memory. Images are harder to shake than prose, especially for young viewers.

This is why the sadness of the film often feels more like trauma, whereas the book’s sadness feels more like reflection. One pierces instantly, the other lingers quietly.

Shared Sadness Across Both

Despite their differences, the book and film share certain elements of sadness that give Watership Down its enduring reputation.

- The Black Rabbit of Inlé: Both versions present death not just as an event, but as a presence — inevitable, inescapable, and even dignified.

- Exile and destruction: The rabbits’ home is destroyed, forcing them into exile. In the book it is a slow, creeping horror. In the film it is a terrifying rush of machines and collapsing earth.

- Violence as part of survival: Predators, traps, and war with other warrens remind us of the precariousness of life.

- Beauty alongside sorrow: Adams’ prose is rich with descriptions of the countryside, and the film captures this in moments of stillness. Sadness is always set against beauty, which makes it more poignant.

Why Do We Still Search “Watership Down Sad”?

Decades later, people still type that phrase into search bars. Why?

First, nostalgia plays a role. Those who watched the film as children often recall it as their first encounter with death and violence. They search now, as adults, to make sense of why it felt so devastating.

Second, Watership Down has become cultural shorthand for “too dark for children.” Alongside The Animals of Farthing Wood and The Plague Dogs, it is cited whenever people discuss disturbing childhood media.

Finally, the story endures because of its honesty. It does not soften the edges of life. Rabbits die. Homes are lost. Leadership carries cost. In a world of sanitised children’s entertainment, Watership Down’s sadness feels strangely authentic — and authenticity, even painful, resonates.

Book vs. Film — Which Sadness Endures?

So which sadness lasts longer: the reflective melancholy of the novel, or the visceral trauma of the film?

The answer may depend on age. Children exposed to the film often remember only the trauma. For many, it overshadowed any allegory or lesson. Adults who revisit the book, however, discover deeper layers: a meditation on leadership, exile, and the inevitability of death.

The film’s sadness is immediate, sharp, and unforgettable. The book’s sadness is enduring, thoughtful, and ultimately more rewarding.

Both matter. One haunts. The other teaches.

Conclusion

Yes, Watership Down is sad. But it is not sad in the same way across mediums.

- The book’s sadness is slow and philosophical, teaching us about mortality, resilience, and the fragile beauty of life.

- The film’s sadness is shocking and visual, leaving scars on the children who weren’t ready for it.

Together, they explain why Watership Down remains one of the most haunting stories of the last fifty years. It is both a tale of survival and a meditation on loss — and whether read or watched, it lingers.

“How can the light that burned so brightly

Suddenly burn so pale?”

The sadness of Watership Down is that all lights eventually dim — but in remembering, retelling, and revisiting, we keep them glowing just a little longer.

Further Reading

- Richard Adams, Watership Down (Penguin, 1972).

- Roger Ebert’s 1978 review: “Beautiful, but with a violence unusual in animation.”

- The Independent (2016) interview with Adams: “I just made it up for my girls.”

- Catherine Lester, Watership Down and the Trauma of Animated Violence, Journal of Film & Screen Studies.